By Sophie Arthur

April 2, 2020

Time to read: 6 minutes

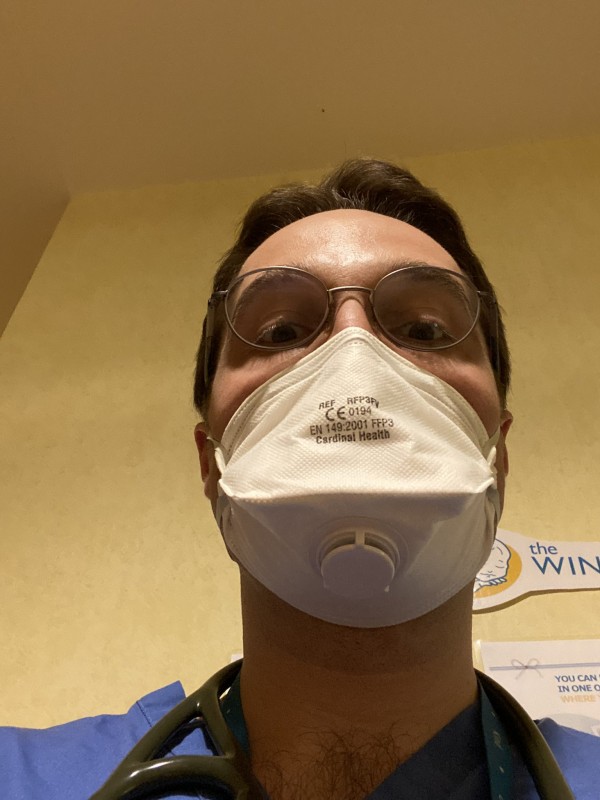

We are extremely proud of all our colleagues who are contributing to the COVID-19 emergency response. We want to celebrate them by highlighting their contributions over the next few weeks in this mini-series of ‘LMS Emergency Response to COVID-19’. Today we want to introduce you to clinical researcher Dr Harry Leitch.

What is your current role within the NHS for the COVID-19 response?

Normally, 50% of my time is spent as a specialist registrar in Clinical Genetics. I have kept my Clinical Genetics clinics going, although most are over the phone for the time being. In addition, I volunteered to give up my academic time to return to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), where I will work between St. Mary’s Hospital and Queen Charlotte’s & Chelsea Hospital as a neonatal registrar. Although babies and children seem to be overall less severely affected by COVID-19, some do still become unwell. There are also many staff who are ill or self-isolating. In addition, neonatal doctors have to attend deliveries from COVID-19 positive mothers, if the baby requires resuscitation or is premature – which perhaps explains some of the transmission to staff in this specialty. I’m also trying to plug other gaps as they emerge and today have done a long day on the paediatric haematology ward, where a number of patients are still recovering from bone marrow transplants. I previously worked on this ward for six months in 2018 – so don’t worry, I’m in familiar surroundings, and not totally out of my depth. A nice thing about going back to old haunts is catching up with colleagues who I worked some pretty tough shifts with, and from whom I learned a lot. I’ve also helped with a few genetic diagnoses already – so I am using my current day job too.

How do you envision that current role might change?

I am happy to adapt to the needs of the NHS – but I am trying to help out where my skillset is most useful, or in roles I’ve worked before. If I hadn’t specialised in Clinical Genetics, I would have liked to do neonatology and so I am enjoying being back looking after wee babies. I may well increase my time in this acute role or be redeployed elsewhere – whatever I can do to help.

How are you balancing this with leading your research group?

It has been a tough adjustment – as I think it has for most wet lab scientists swapping to home working. We are keeping our normal weekly meetings, and I try to meet with people 1:1 as much as possible – all via Zoom of course. My lab have been very accommodating and happy to meet after a shift in the evening, if necessary. We have also tried to have some social meetings too. With regards to admin tasks, I’m just trying to deal with emails in quiet moments – and watching my iPhone like a hawk. Sorry to those people who have had to give me a few prods. We may do some extra journal clubs so that my lab keep up to date with literature. Many non-medics will have responsibilities at home – childcare, home schooling, looking after relatives etc – which are probably just as challenging. And some people have both – which sounds absolutely terrifying. I think we all just have to muddle on and do the best that we can.

Is there anything you have learnt from leading your research group that you are applying now back at the NHS?

I’m in a more senior role in the research setting than I am on the wards. Sometimes it’s quite nice not to be the boss, and have someone tell you what to do. Also, this probably makes me feel more comfortable asking stupid questions, and contributing ideas to discussions. Although I am very mindful of not getting ideas above my station – and learning from the people who do this job full time. In many ways, research and clinical work are two separate worlds though; it’s rare I apply my knowledge of pluripotency on the wards.

Is there anything else you want to share about your experience ‘on the front line’?

It’s been great to see the support from frontline workers and the NHS staff – both clinicians and those critical non-clinical team members. I really hope the good will from the public and politicians continues after the crisis. The last few years have been extremely tough on the NHS, and after crisis mode has subsided there is a lot of support and investment needed across the board.

Tell us a little bit about you

I was born in Scotland. I did an MB/PhD at Fitzwilliam College, University of Cambridge. This involves doing a medical degree and a PhD in combination. In total, I spent 11 years at medical school… luckily I started before the introduction of tuition fees. I have also represented Scotland at the Commonwealth Games playing squash.

What is your work history before moving to clinical research?

I worked my first year as a junior doctor (Foundation Year 1) in East of England, at West Suffolk Hospital before moving to London to take up an academic Foundation Year 2 post, part of the Chain-Florey scheme at the LMS. Since then, I have gradually grown my research group at the LMS, firstly as an Academic Clinical Fellow in Paediatrics, and now as an Academic Clinical Lecturer in Clinical Genetics.

What is your lab group’s research on?

I head the Germline and Pluripotency lab. We study how cells of the early embryo can develop into all the different tissues in the adult body. In particular, we are interested in the cells that establish the germline – the precursors cells of sperm and egg. Without these crucial cells, we would not be able to have children, and pass on our genes to the next generation. Our focus is on fundamental discovery science but our work does have important implications for medically important problems – such as infertility and paediatric cancer.

Harry was also featured in a piece by Cell Stem Cell about early career stem cell researchers impacted by COVID-19. You can read the piece here.