By Helen Figueira

June 18, 2015

Time to read: 3 minutes

Deborah Oakley

Picture a heart that is ‘baggy’ and stretched on one side. Its thin muscle is too weak to pump blood around the body. This disease, called dilated cardiomyopathy, affects 1 in 250 people and can lead to sudden death. Earlier diagnosis may help to save lives.

This week, cardiologist James Ware visited the MRC’s Clinical Sciences Centre (CSC) to tell scientists the latest in his quest to understand the genetics of the disease.

Dilated cardiomyopathy is caused by mutations in a gene that produces a protein, called titin. It is the largest protein in the human body, and acts like a spring within muscle tissue, including the heart.

Titin’s size is crucial to its function, but in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy it is abnormally small and cannot function correctly. The protein’s size is altered because the patients have a mutation in the titin gene. But as many as 1 in 50 people have similar mutations and remain healthy. “That really threw a spanner in the works,” said Ware. By examining the differences between the two groups, he’s been able to identify the exact genetic changes that make the protein shorter, and lead to disease.

“We can use this information to screen patients’ relatives to identify those at risk of developing the disease, and help them to manage their condition early,” says Stuart Cook, who leads the CSC’s Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Genetics research group, and who led the study.

Ware has been awarded a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellowship, and will be working with Cook. The pair first worked together in 2008, while Ware was completing his PhD at the CSC. After graduation he continued his research at Harvard University.

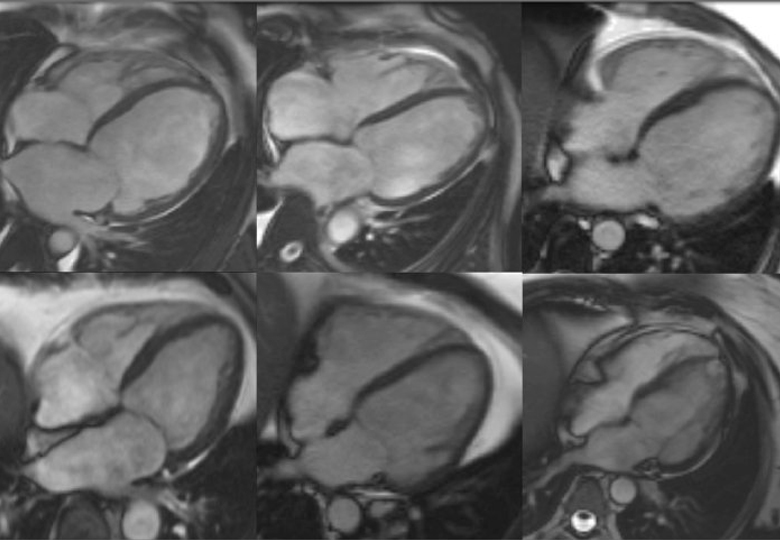

They now aim to find out more about the role of titin in the healthy heart by creating 3D images using the cutting-edge magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) facilities in Hammersmith Hospital, the first place in the world to have a commercial MRI scanner. “We also hope to carry on with our gene discovery projects, particularly early onset childhood dilated cardiomyopathy,” said Ware. If scientists can find out more about titin, they may one day be able to develop ways to replace the shorter protein and help to treat dilated cardiomyopathy.

Read Imperial College London’s news story about Ware’s latest research (http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/newsandeventspggrp/imperialcollege/newssummary/news_14-1-2015-13-56-53). Here’s his latest paper (http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/7/270/270ra6.full).

For further information, contact:

Deborah Oakley

Science Communications Officer

MRC Clinical Sciences Centre

Du Cane Road

London W12 0NN

T: 0208 383 3791

M: 07711 016942

E: