By Helen Figueira

December 18, 2015

Time to read: 5 minutes

Deborah Oakley

They’d warned me about the noise. But its sudden banging and pounding took me by surprise. It felt so close, so intense, that I thought the machine had broken. I wanted to escape. With my heart pounding, I closed my eyes and imagined lying on a beach.

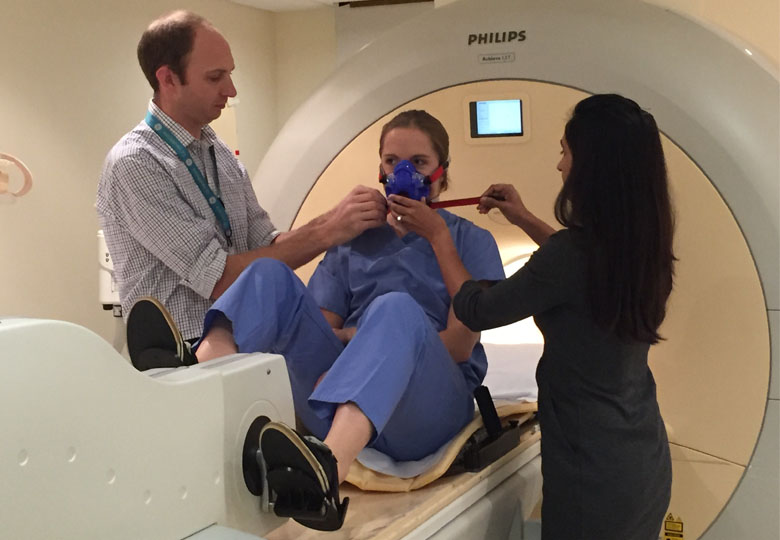

In reality, I was lying inside a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanner. The barrel of the chamber curved just centimetres above my face, a plate lay on my chest and straps held me in position. With each breath I could taste the rubber mask that was supplying me with air lacking in oxygen. And all this while pedalling on a horizontal bike. Being at the cutting edge of science is less glamorous than it sounds.

The unique set-up was part of a research study that is one of the first in the world to use an MRI scanner to take images of the heart in ‘real time’ while a person exercises and breathes in air that contains less oxygen than normal. At sea level, air contains 21% oxygen and a mix of other gasses. I was breathing in air with just 12% oxygen, that’s about the same as a climber breathin in at the peak of the Alps.

The discomfort was worth it because understanding how the hearts of healthy people like me compensate to handle this stress could help the researchers to develop a more accurate way to diagnose heart conditions.

Patients with these conditions often tell the researchers that they experience their symptoms while walking around. But most diagnostic tools require patients to sit still, and can’t provide detailed images of the heart during exercise. The team, at the MRC Clinical Sciences Centre (CSC) at Imperial College London and Hammersmith Hospital, are aiming to develop a more accurate technique by fine-tuning the use of MRI scanners.

“Patients are enthusiastic to take part in the study, because it makes sense to them – they experience their symptoms during exercise, so it’s logical to examine their heart during exercise too,” says Shareen Jaijee the cardiologist who leads the research. “It can be unpleasant inside the scanner, but we tried it ourselves before asking patients and volunteers to take part. So far we’ve had 29 volunteers and 13 patients participate, and we’ve got some interesting early results.”

As I felt my heart pound in my chest, behind the viewing screen George Freeman, Minister for Life Sciences, was watching everything live on a computer screen.

Freeman was visiting the CSC to learn more about our research and how it might best be translated from the laboratory into advances in healthcare.

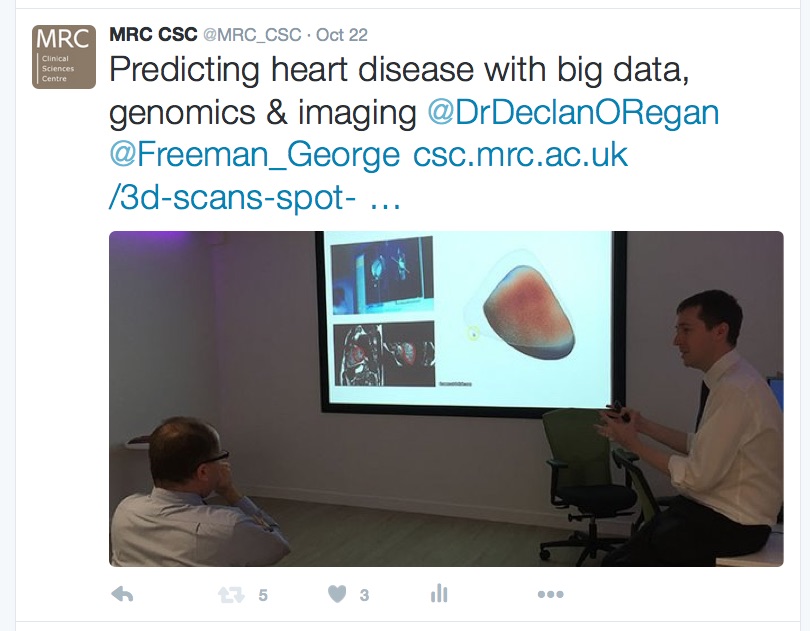

As I cycled inside the scanner, Freeman sat comfortably and listened to Declan O’Regan, who leads the CSC’s MR Facility, explain how his research combines world-leading imaging techniques with data from genetic sequencing to try to predict an individual’s risk of heart disease.

O’Regan and colleagues have used MRI scans and the latest computer technology to create 3D maps of the hearts of 1500 people. In recently published findings they’ve shown that this mapping technique can spot subtle changes in the heart. At the time O’Regan said, “These scans show the earliest signs of heart disease may begin in completely healthy people.”

Freeman’s tour extended beyond the realm of hearts and imaging, and into the research laboratories. He met James Leiper who leads the Nitric Oxide Signalling group, and who works on sepsis, a life-threatening condition caused by infection that kills around 37, 000 people in the UK every year. Leiper has recently been awarded a grant to take a potential drug to treat sepsis into human trials.

Freeman also explored the CSC fly lab where Irene Miguel-Aliaga (right), who leads the Gut Signalling Metabolism group, explained how research in flies can teach us about the basis of cancer and obesity in people.

After meeting Miguel-Aliaga, Leiper and O’Regan, who are all senior scientists, Freeman was introduced to the younger generation (below). A group of PhD students, post-doctoral researchers and Chain-Florey Fellows and Lecturers outlined their work and its importance. The CSC’s Chain-Florey scheme gives doctors the opportunity to undertake research in science laboratories. Freeman described them as “Nobel-prize winners of the future.”

Back in the MRI room, I was recovering from the study. My slight claustrophobia made it tough to take part, but my temporary discomfort was nothing compared to the difficulties faced by people with heart conditions every day. I don’t need to look beyond my immediate family to appreciate this. Of course, my scan is just one small part of the on-going research, but it’s great to know that I’ve done what I can to help improve diagnosis and treatment.

——

There are a variety of on-going studies that explore the heart and its function at the Clinical Sciences Centre. To take part contact ">Shareen Jaijee.

For further information, contact:

Deborah Oakley

Science Communications Officer

MRC Clinical Sciences Centre

Du Cane Road

London W12 0NN

T: 0208 383 3791

M: 07711 016942

E: