For more information, contact:

Deborah Oakley

Science Communications Officer

MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences

M: 07711 016942

T: 0208 383 3791

E:

T: @MRC_LMS

People with heart disease feel empowered when they take part in medical research, say patients who met with scientists at the MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences (LMS).

By Helen Figueira

June 14, 2017

Time to read: 4 minutes

By Deborah Oakley

People with heart disease feel empowered when they take part in medical research, say patients who met with scientists at the MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences (LMS).

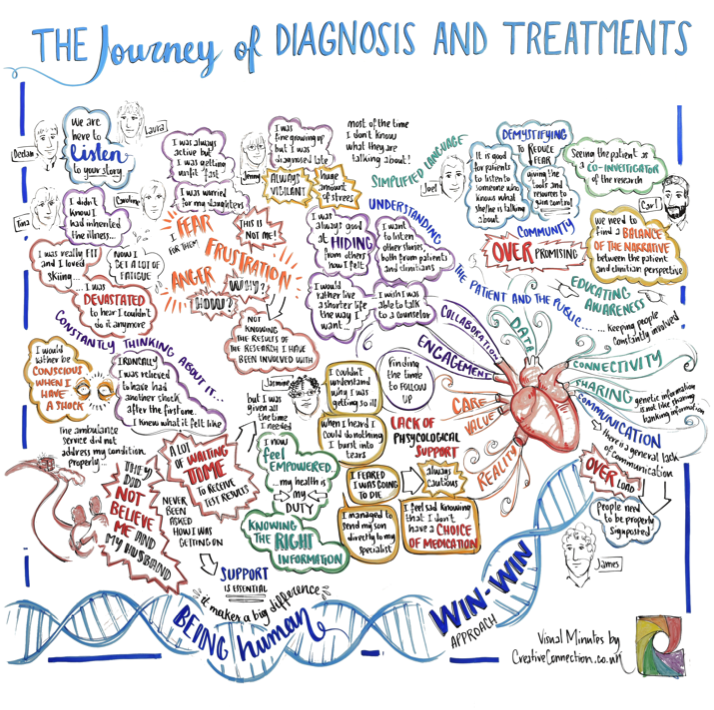

The two groups came together to discuss how to improve research on heart disease. Patients heard about the latest advances, such as using artificial intelligence to improve diagnosis, and researchers listened to what it’s really like to live with an inherited heart condition. Whilst they talked, an artist sketched “visual minutes” to capture the patients’ hopes and fears.

“The session highlighted both challenges and opportunities for clinicians and researchers. We need to develop the way we communicate with patients, and the psychological impacts of disease need even more recognition and support in the clinic,” says James Ware, a senior lecturer who explores the genetics of heart disease at the LMS, and who is also a cardiology consultant. “Encouragingly, many patients are highly motivated to engage with research, and would welcome increased opportunities for participation.”

However, some patients said while there are opportunities to become involved in research studies at specialist centres, such as Hammersmith Hospital, this is not the experience of patients everywhere. Such opportunities are not typically mentioned during routine appointments, said Tina, who has lived with a heart condition for over ten years. Although she has been involved in several studies, she said that she found out about these only by accident. Study recruitment should be better integrated into clinical care, agreed the patients and researchers. Together they considered when would be the best moment to recruit patients and suggested around a month after an individual’s initial diagnosis, to give people time to absorb what can be distressing news.

Today, researchers have no single comprehensive list of interested volunteers they can turn to when seeking participants. Tina suggested setting up a database of patients and healthy volunteers who would happy to be contacted by researchers across the UK. Ware said patient confidentiality would need to be ensured, and that sharing data can be challenging because hospitals often store data in different formats. He says, “Collaborative sharing of data is key in contemporary science, though can perceived as challenging. But we found that patients are keen supporters of more open science. Greater involvement of patients as co-investigators should only improve the quality of the research we do.”

Being “co-investigators”, rather than simply participants, would allow patients to bring unique insights to a study, they said. Key to being truly involved is being informed of the results of studies, said Caroline who has been recently diagnosed. Patients with inherited conditions are particularly keen to hear of any advances that might one day help their children, for example, as they may go on to develop the condition.

“It was encouraging to hear that patients with inherited cardiac conditions feel empowered by being involved in research. We now need to find more effective ways to share information between healthcare providers, researchers and patients,” says Declan O’Regan, who studies mathematical models of the heart at the LMS, and who is also a consultant radiologist.

LMS research nurse Laura Garcia, who organised the session in March, said, “It was a great experience to listen to patients with inherited cardiac conditions. Our group members explained that the language used during consultations is very important and can often have serious implications for patients. The term ‘heart failure’, for instance, invokes a fear reaction and can be conceptualised as a death sentence.”

Around one in three people develop depression or anxiety after their initial diagnosis, said Jenny who has had a heart condition since childhood. Jenny is exploring the experience of diagnosis and how to improve as part of her PhD research.

The event was funded by the NIHR Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre.

For more information, contact:

Deborah Oakley

Science Communications Officer

MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences

M: 07711 016942

T: 0208 383 3791

E:

T: @MRC_LMS