Humans are made up of billions of cells, all of which need to divide in a regulated manner. Each time a cell divides, the DNA within that cell needs to be accurately replicated. If new cells contain extra copies of DNA, this can cause diseases such as cancer. To prevent this, the cell uses various mechanisms to ensure that DNA replication only happens once, in each division cycle. New research, led by Lucy Edwardes from the DNA Replication group and Josh Tomkins from DNA Replication group, Cell Cycle Control group and the Barnard group (Imperial, Department of Chemistry), has shone light on how the DNA replication inhibitor geminin physically blocks DNA replication from happening at the wrong times.

Regulating DNA replication

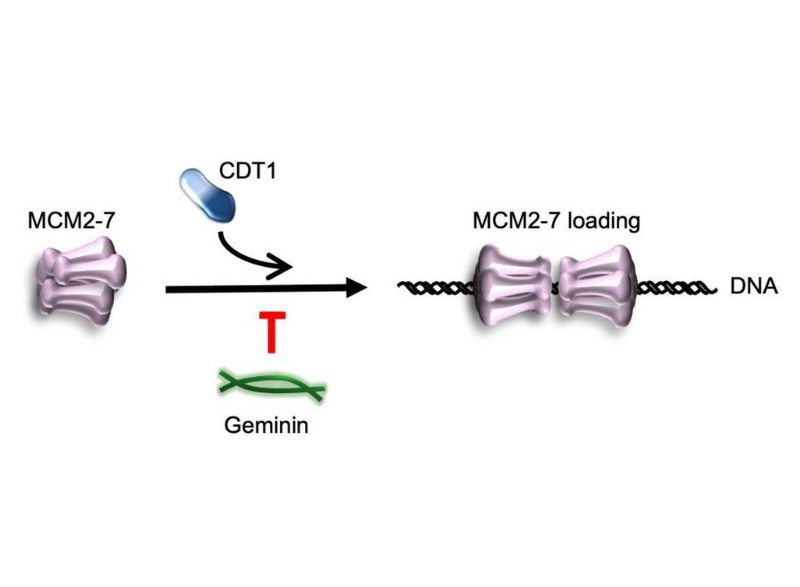

For DNA replication to take place, a protein complex called MCM2-7 is required. MCM2-7 acts as a helicase, a type of protein that can unzip DNA, allowing it to be read and copied. MCM2-7 needs to work with other proteins, such as CDT1, to be loaded on DNA and unzip DNA. By regulating interactions between MCM2-7 and CDT1, geminin enables the cell to quickly and tightly control DNA replication.

How does geminin prevent DNA replication?

Researchers previously assumed that geminin would prevent DNA replication by binding CDT1 in the same location as MCM2-7. This would stop CDT1 from binding MCM2-7 as the space would already be occupied. As only some parts of the CDT1-geminin complex’s structure were known, the team used AlphaFold, an AI tool that predicts protein structure, to model the rest. The AI predictions were then tested using fragments of protein which mimicked different regions of geminin, to find which parts bound to CDT1. The team showed that the CDT1-geminin and CDT1- MCM2-7 interaction regions did not overlap, highlighting that another region of geminin physically blocks CDT1 from binding MCM2-7. The region of geminin responsible for this block is known as a coiled-coil, a protein structure composed of 2 or more chains which spiral around themselves. Shortening of the coiled-coil stopped geminin from inhibiting DNA replication.

Despite geminin inhibiting helicase binding to the DNA, ~15% of MCM2-7 loading still occurred in its presence.

So, what would be required to completely block DNA replication?

The team discovered that a two-pronged approach is needed. A protein called CDK1, which modifies proteins during the cell division cycle, was required to inhibit MCM2-7 loading completely. Thus, the team has found that at least two factors are needed to avoid re-replication. This research was made possible by previous work from the DNA replication group, headed by Professor Christian Speck. In their prior work, the team reconstituted the human DNA replication machinery for the first time. “Studying human proteins is essential because much of the earlier research has been done in yeast,” says Lucy, “Yeast differs significantly from human cells. For instance, it doesn’t have geminin. By studying the human version, we’ve not only learned more about how geminin works, but also confirmed the validity of the human system we recently developed.” “In cancer and during ageing, the control of DNA replication gets altered,” says Christian, “the cross-departmental team has unravelled how the start of DNA replication gets controlled and this information will be crucial for clinicians to understand how the transformation of healthy cells into cancer cells affects genome stability.”

Potential for novel cancer therapies

The team also hopes that this work could help lead to the development of new therapeutics in the future. Geminin could be a new target for anti-cancer therapies as it has the potential to modulate DNA replication in the cell cycle, halting cell division. “Geminin plays a crucial role in cancer because of its ability to control DNA replication,” says Josh, “By uncovering how geminin functions, we move closer to discovering therapies that can mimic or disrupt its function to selectively target tumour cells.”

This work was funded by Cancer Research UK, the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society.

Read the full publication: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67073-0