By Helen Figueira

September 24, 2013

Time to read: 3 minutes

New hope for sufferers of TBI

New hope for sufferers of TBI

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a prominent cause of death and disability around the globe. In the UK around 1 million people attend A&E following head injury annually with many more going unreported. Long-term effects of TBI include headaches, lethargy, poor memory and concentration, low mood and even personality changes. In the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, blast injury is the leading cause of death due to munitions such as Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs). Improved protective equipment and medical management of severe trauma has increased numbers of surviving soldiers who would previously have died.

Now new collaborative research from the CSC shows the potential long-term effects of blast TBI on cognitive, psychological and hormonal function. Tony Goldstone a Senior Clinician Scientist in the Metabolic and Molecular Imaging Group at the CSC and Consultant Endocrinologist at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, together with Professor David Sharp and Major David Baxter of Imperial College London, collaborated on the study.

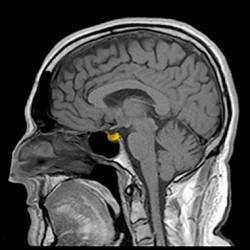

“Over the last few years there has been increasing evidence that people who have TBI, are at risk of pituitary dysfunction resulting in hormone deficiencies,” explains Goldstone. “But we didn’t know whether this was a significant problem after blast TBI, so our study compared people with a high severity of TBI due to blast and other causes. We were very thorough and used multiple endocrine tests to confirm the presence of hormone deficiencies.”

19 male soldiers with a single moderate-severe blast TBI from an IED in Afghanistan and 39 men with moderate-severe non-blast TBI (e.g. from road traffic accidents, falls, assaults) were included in the study. Both groups had full dynamic endocrine assessments between 2 and 48 months after injury. The results showed that there was a high prevalence of anterior pituitary dysfunction after blast TBI, with the soldiers being more likely to suffer from pituitary dysfunction than the non-blast TBI group (32% vs. 2.6%).

“Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a really useful tool,” Goldstone asserts,” it shows how much damage has been caused to the white matter tracts that run throughout the brain by measuring water flow. Soldiers with pituitary dysfunction had significantly more damage to certain white matter tracts, than those without hormone problems.”

Soldiers with pituitary dysfunction were more likely to have skull and facial fractures, and had more severe cognitive problems. “Brain injury is more severe in soldiers with hormone problems, which may also impact on brain recovery and function”, adds Goldstone. 21% of the soldiers with blast TBI needed hormone replacement therapy, including growth hormone, hydrocortisone or testosterone. “The results look promising. Hormone replacement really seems to help. We will follow up with a longitudinal study over the coming year,” says Goldstone.

The study is evidence for routine assessment of endocrine function in soldiers with moderate to severe blast TBI. “That way we can identify patients who may benefit from hormone therapy,” Goldstone adds. “The findings of this study will hopefully alleviate the long-term effects of blast trauma and influence the care available for military and civilian patients following such incidents.”

MT