By Helen Figueira

April 22, 2016

Time to read: 5 minutes

Deborah Oakley

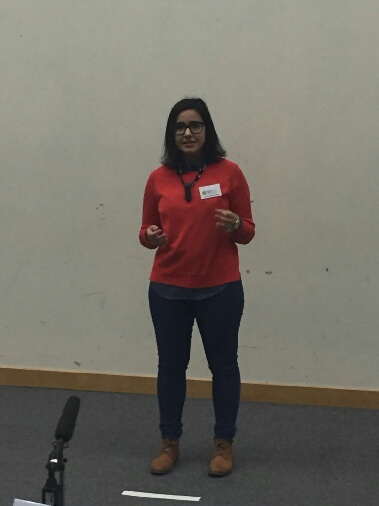

“The cell makes one of the most fundamental decisions in the time it takes for us to wait for a bus,” said Alix Gunne-Braden of the MRC Clinical Sciences Centre (CSC). She was discussing how the cells in a developing embryo are under pressure to decode signals from their environment, and how they use these to make an irreversible decision. Gunne-Braden had just three minutes to explain this complex cell biology, to an audience of non-specialists.

She was one of 18 PhD students from Imperial College London taking part in the 3 Minute Thesis competition yesterday afternoon. Also competing was Ana Rita Carvalho Araujo who works with Gunne-Braden in the CSC’s Quantitative Cell Biology group.

If Gunne-Braden felt under pressure, she didn’t show it. She smoothly navigated around the technical jargon and abbreviations common in her field. She explained that cells in an early embryo must decide which type of specialised cell, such as a heart, skin or nerve cell, they will become. “Given the magnitude of this decision, the cell should take its time and carefully weigh up its options before committing to a process with such widespread ramifications,” said Gunne-Braden. But her research shows that this is not the case. In fact, the cells take just minutes to decide.

Araujo discussed another unexpected finding. She contrasted the life cycle of a cell with that of a butterfly. Just like a butterfly passes through different phases – beginning as an egg that grows into a worm and then develops into a colourful butterfly – the cells in our bodies pass through different stages. She explained that scientists do not fully understand the role that time plays in this cycle.

In her research Araujo has been surprised to find that a variety of cells – including stem cells and cancer cells – all spend just 45 minutes in a particular stage of the cycle, called mitosis. “This was really unexpected,” said Araujo. She now wants to explore why this happens, and how it is regulated so precisely.

Reflecting on her performance, she said, “It was difficult, perhaps I spoke too quickly. I kept looking at one of the judges in the front row because she was always smiling. It calms you down.”

Araujo drew the motivation to compete from her family and friends. “They always ask about my work and I struggle to tell them. Explaining your science is hard,” she said.

Gunne-Braden agreed, and said it’s important to devote time to develop communication skills. She expects that such skills will prove crucial when she comes to explain her research to future colleagues and collaborators – in her scientific career and beyond.

“It’s important to be able to explain your work to people from other areas of science,” she said. She added that she was fascinated to learn about the other competitors’ research, and the work taking place in other parts of Imperial College. She said she values conversations with people working in different areas of science.

The competitors were judged by a panel that included last year’s winner, Ryan Robinson, and the British Science Association’s public engagement manager, Rosie Waldron.

Winner Sophie Danny discussed her research on train travel. She began by imitating an announcement about a train delay. “Imagine a rail network where trains are where they are supposed to be, when they are supposed to be,” said Danny.

She went on to explain that a new technology has the potential to prevent delays and make train travel more efficient. This technology uses satellites in space to accurately track train movements in real time. But the satellite signals can be blocked when trains travel under bridges, electrical wires and through urban areas. Danny used a cartoon that she had drawn to explain how her work could help to overcome these hurdles. She said that she wants to transport train travel into the space age.

In second place, and with another cartoon drawing, was Taran Driver who studies proteins. Driver said that proteins are like words. Each word is composed of a sequence of letters chosen from a pool 26 possible letters. Proteins are a sequence of small molecules, called amino acids, and there are 20 amino acids to choose from.

He said that proteins are the biological workhouses of the body. But if an amino acid is damaged, a protein may no longer be able to carry out its function. Driver said that current technology cannot detect exactly which amino acid in the sequence has been damaged. He is developing a laser that could split the sequence into its constituent parts in a fraction of a second. This could help scientists to pinpoint the damage.

New this year was the Peoples’ Choice award. Audience members voted for their favourite competitor during the interval. Winner Timo Lauteslager is developing a portable helmet to study brain activity. He said, “I think that by developing new technology such as this, we will get closer to finally understanding our brains.”

For further information, contact:

Deborah Oakley

Science Communications Officer

MRC Clinical Sciences Centre

Du Cane Road

London W12 0NN

T: 0208 383 3791

M: 07711 016942

E: