By Deborah Oakley

Regular use over many years of drugs in a class known as stimulants, including cocaine, is associated with lower levels of the brain chemical dopamine, which plays a key role in how the brain processes reward, motivation and pleasure. This may explain why these drugs are highly addictive, and suggests that targeting dopamine could help to treat addiction, according to a review of current research published this week in JAMA Psychiatry.

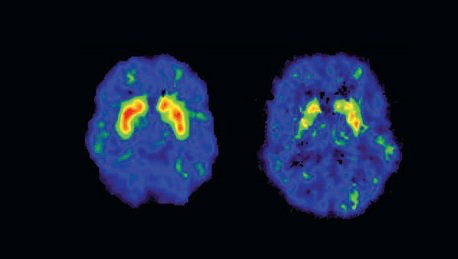

The review was led by Oliver Howes, of the MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences (LMS), and involved examining the action of dopamine through detailed analysis of 31 studies involving brain scans of long-term users of the drugs cocaine, amphetamine, and its close cousin methamphetamine.

Many of these studies used only small groups of people because scanning the brains of drug users is a difficult and sometimes expensive process. By drawing together the results of many such studies, this review draws a clear link between amphetamine, cocaine and methamphetamine use and blunted dopamine levels.

Up to 53 million people globally used amphetamine in 2015, whilst up to 20 million used cocaine, according to the World Drug Report*. Addiction to these drugs is common, but there is no effective treatment, say the researchers.

“One of the reasons for the failure to develop effective treatments might be our lack of understanding about the exact nature of the chemical changes in the brains of long-term users,” says Howes. “There is an urgent need to develop new, and more effective treatments.”

It has been known that when an individual first uses one of these drugs, it raises dopamine levels in their brain and this produces a euphoric feeling, or “high”. This review suggests that after repeated drug use the brain may compensate, by dampening down baseline levels of dopamine. This abnormal brain state may induce a negative feeling, and create the cravings that may drive addiction, says Abhishekh Ashok, also of the LMS, who played a key role in the review.

“If we can develop treatments to restore normal dopamine levels, we may one day be able to treat addiction,” says Ashok. “We may also be able to predict how likely it is that a given person will respond to this treatment by measuring the numbers of dopamine receptors in an individual’s brain.”

These findings add to the conclusions of another review on drugs and dopamine by the same team, published in Nature last November. The study showed that regular, long-term cannabis use blunts levels of dopamine in the brain. Read more here.

The LMS scientists worked with researchers at King’s College London and the National Institute of Drug Abuse, USA.

* World Drug Report 2015, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime