An elegant collaboration between researchers in the UK’s two core-funded Medical Research Council Research Institutes, the Laboratory of Medical Sciences (LMS) in London and the Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) in Cambridge, has solved a decades-old mystery which could pave the way to better cancer treatments in the future.

By LMS Staff Member

July 31, 2024

Time to read: 7 minutes

The work, which uncovered the basic mechanism of how one of our most vital DNA repair systems recognises DNA damage and initiate its repair, has eluded researchers for many years. Using cutting edge imaging techniques to visualise how these DNA repair proteins move on a single molecule of DNA, and electron microscopy to capture how they “lock-on” to specific DNA structures, this research opens the way to more effective cancer treatments.

The collaboration between the laboratories of Professor David Rueda (LMS) and Dr Lori Passmore (LMB) has been a brilliant example of how #teamscience can bear fruitful results and underscores the importance of these two institutes in driving forward research that unlocks the fundamental mechanisms of biology which will underpin the future translation of that work into improvements in human health.

The researchers were working on a DNA repair pathway, known as the Fanconi Anaemia [FA] pathway, which was identified more than twenty years ago. DNA is constantly damaged throughout our lives by environmental factors including UV light from the sun, alcohol use, smoking, pollution and exposure to chemicals. One way in which DNA becomes damaged is when it is “cross-linked”, which stops it being able to replicate and express genes normally. In order to replicate itself and to read and express genes, the two strands of the DNA double helix first has to unzip into single strands. When DNA is cross-linked, the “nucleotides” (the “steps” in the double-helix ladder of DNA) of the two strands become stuck together, preventing this unzipping.

The accumulation of DNA damages including cross-linking can lead to cancer. The FA pathway is active throughout our lives and identifies these damages and repairs them on an ongoing basis. Individuals who have mutations that make this pathway less effective are far more susceptible to cancers. Although the proteins involved in the FA pathway were discovered some time ago, a mystery remained over how they identified the cross-linked DNA and started the process of DNA repair.

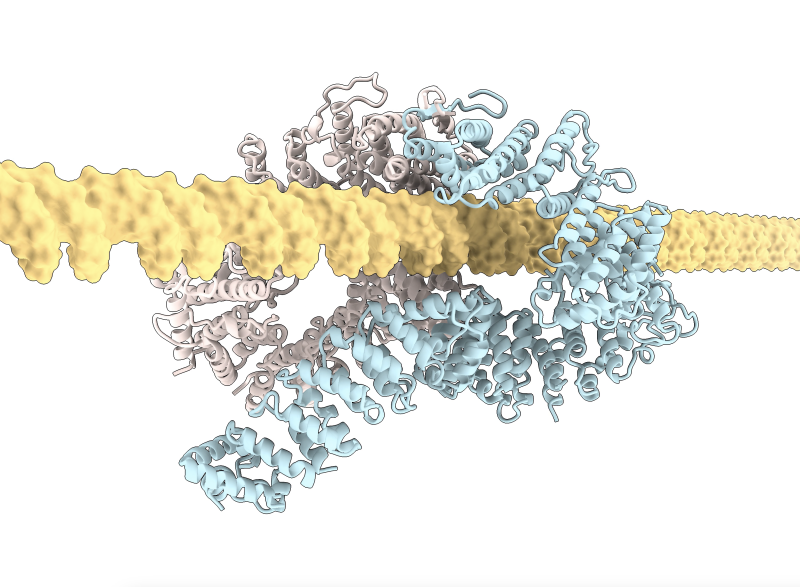

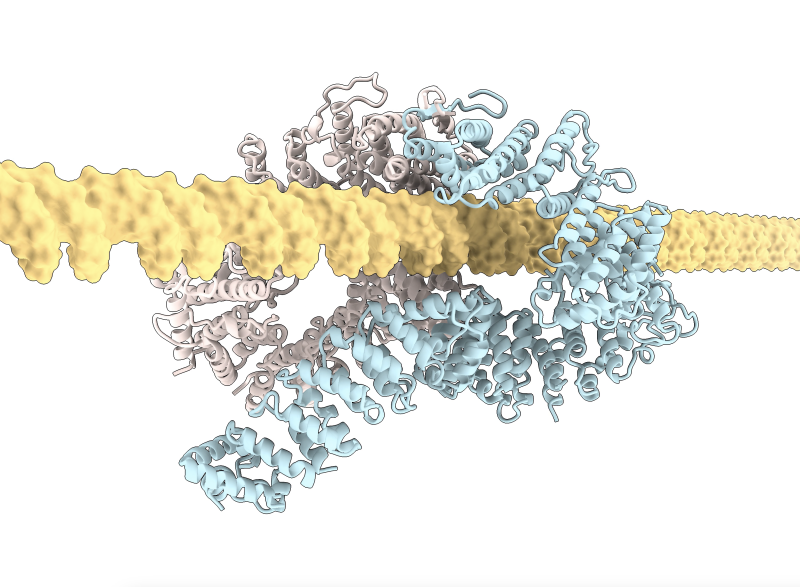

The team from the MRC LMS sister institution, the LMB in Cambridge, led by Lori Passmore, had previously identified that the FANCD2-FANCI (D2-I) protein complex, which acts in one of the first steps of the FA pathway, clamps onto DNA, thereby initiating DNA repair at crosslinks. However, key questions remained: how does D2-I recognise crosslinked DNA, and why is the D2-I complex also implicated in other types of DNA damage?

Today’s publication in Nature has used a combination of cutting-edge scientific techniques to show that the D2-I complex slides along the double-stranded DNA, monitoring its integrity, and has also elegantly visualised how it recognises where to stop, allowing the proteins to move and lock together at that point to initiate DNA repair.

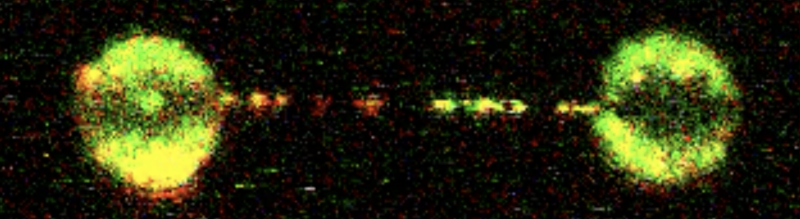

Artur Kaczmarczyk and Korak Ray in David Rueda’s Single Molecule Imaging group, working with Pablo Alcón in Lori Passmore’s group, used a state-of-the-art microscopy technique known as “correlated optical tweezers and fluorescence imaging” to explore how the D2-I complex slides along a double-stranded DNA molecule. Using optical tweezers, they could catch a single DNA molecule between two beads, which allowed them to precisely manipulate the DNA and incubate it with chosen proteins. Using fluorescently labelled D2-I and single-molecule imaging, they observed how individual D2-I complexes bind to and slide along DNA, scanning the double helix. They discovered that rather than recognising the crosslink between the two strands of DNA directly, the FA clamp instead stops sliding when it reaches a single-stranded DNA gap, a region where one of the two strands of DNA is missing.

Using cryo-electron microscopy, a powerful technique which can visualise proteins at a molecular level, the researchers next determined the structures of the D2-I complex both in its sliding position and stalled at the junction between single-stranded and double-stranded DNA. This revealed that the contacts D2-I makes with this single-stranded–double-stranded DNA junction is distinct from the contacts it makes with double-stranded DNA alone. This allowed them to identify a specific portion of the FANCD2 protein, called the “KR helix” that they showed in their single-molecule imaging experiments is critical for recognising and stalling at the single-stranded DNA gaps. Working with Guillaume Guilbaud and Julian Sale in the LMB’s PNAC Division, and Themos Liolios and Puck Knipscheer at the Hubrecht Institute, Netherlands, they further showed that the D2-I complex’s ability to stall at these junctions using the KR helix is critical for DNA repair by the FA pathway.

When DNA normally replicates in our cells, it unzips the two DNA strands and copies each single strand. This creates a ‘replication fork’ where the original DNA strands are unwound and new double-stranded DNA is formed on each strand. However, when this fork reaches a DNA crosslink, the strands cannot be unzipped, stalling the usual DNA replication process. This stalled replication fork thus contains exposed single-stranded gaps where the DNA has been unwound but not replicated. This research has shown that it is these junctions between single- and double-stranded DNA at the stalled replication fork that the D2-I protein complex latches tightly onto. Not only does this allow D2-I complex to bring other FA pathway proteins to the DNA crosslink to initiate repair, but it also anchors the remaining double-stranded DNA, protecting the stalled “replication fork” from enzymes in the cell that would chew up the exposed end of the DNA strand and further damage the DNA. This work has shown that it is DNA structures within the replication fork that stalls as a result of cross-linked DNA, rather than the cross-linked DNA itself, that triggers the D2-I complex to stop sliding and clamp on to DNA to initiate repair. These stalled replication forks appear in many types of DNA damage, explaining the broad role of the D2-I complex in other forms of DNA repair as well as via the FA pathway.

Understanding the process of DNA repair, and, importantly, why it fails, holds huge importance as DNA damage is a key factor in many diseases. Critically, many cancer drugs, for example Cisplatin, work by inducing such serious cellular damage to cancer cells that they stop dividing and die. In such cases, DNA repair pathways—such a vital physiological process in normal life—can be hijacked by cancer cells who use them to resist the effects of chemotherapy drugs. Understanding the mechanistic basis of the first step in the DNA repair pathway may lead to ways of sensitising patients so that cancer drugs can be more effective in future.

This work was funded by UKRI MRC, the Wellcome Trust, the European Research Council and EMBO.

Read the article in Nature