Understanding how the short-chain fatty acid acetate can curb appetite.

Understanding how the short-chain fatty acid acetate can curb appetite.

Bestowed upon us from the Stone Age, a diet high in resistant starch fibres, found in chickpeas, black beans and lentils, have been unequivocally linked to reduced body weight and subsequently lower incidences of heart disease and diabetes. Now – millennia later – with sugary and fatty foods ungrudgingly accessible and lifestyles warranting little physical activity, obesity is vast becoming the social norm in western society. Today, a breakthrough from Professor Jimmy Bell (Group Leader for the CSC’s Metabolic and Molecular Imaging Group and obesity specialist at Imperial College London) and his team, in collaboration with Professor Gary Frost (Imperial College London) and Professor Sebastian Cerdan (Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas, Madrid), detail a novel role for resistant starch fibres in controlling appetite, which promises to impact obesity prevention and treatment.

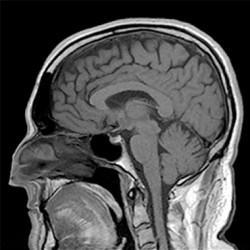

Published in Nature Communications, the study reveals that resistant starch dietary fibres are fermented in the colon to release high concentrations of the short-chain fatty acid acetate, which are left circulating in the blood. By labelling the acetate, the group tracked its journey to the brain. “Mice on high resistant starch diets had higher acetate levels, and through imaging studies we saw changes in brain activity. From analysing brain tissue we were able to see elevated levels of acetate in the hypothalamus,” explains Jimmy.

The acetate triggered some of the so-called ‘hunger neurons’ associated with food suppression, and consequently a reduced food intake was observed in mice. “This is a novel mechanism explaining how dietary fibres actually work; simply increasing the levels of acetate circulating in the hypothalamus reduces food intake,” says Jimmy.

Our ancestors would consume an estimated 100 grams of dietary fibres per day. Jimmy’s group showed that the human equivalent to 30-40 grams per day was enough to see reduced food intake in mice. “The implications of this study are that high dietary fibres will supress appetite longer term during the day, resulting in a reduced calorie intake,” he adds.

Though, as the saying goes, ‘Beans, Beans, They’re Good for your Heart,’ a high intake of dietary fibres can be conducive to some discomfort. The next step for the team involves developing a high concentration short-chain fatty acid supplement and taking the investigations further into humans. “For us this is really exciting, as now we have made the link between population studies, all the way into molecular studies and to understanding human responses.”

YJ

Reference: Frost, G., Sleeth, M. L., Sahuri-Arisoylu, M., Lizarbe, B., Cerdan, S., Brody, L., Anastasovska, J., Ghourab, S., Hankir, M., Zhang, S., Carling, D., Swann, J. R., Gibson, G., Viardot, A., Morrison, D., Louise Thomas, E., & Bell, J. D. (2014). The short-chain fatty acid acetate reduces appetite via a central homeostatic mechanism. Nature Communications, 5, 3611.

Featured in The Telegraph, Nature and Scientific American.

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council.

The Medical Research Council has been at the forefront of scientific discovery to improve human health. Founded in 1913 to tackle tuberculosis, the MRC now invests taxpayers’ money in some of the best medical research in the world across every area of health. Twenty-nine MRC-funded researchers have won Nobel prizes in a wide range of disciplines, and MRC scientists have been behind such diverse discoveries as vitamins, the structure of DNA and the link between smoking and cancer, as well as achievements such as pioneering the use of randomised controlled trials, the invention of MRI scanning, and the development of a group of antibodies used in the making of some of the most successful drugs ever developed. Today, MRC-funded scientists tackle some of the greatest health problems facing humanity in the 21st century, from the rising tide of chronic diseases associated with ageing to the threats posed by rapidly mutating micro-organisms. www.mrc.ac.uk