By Helen Figueira

February 28, 2014

Time to read: 4 minutes

Understanding the link between dopamine and psychotic traits

Understanding the link between dopamine and psychotic traits

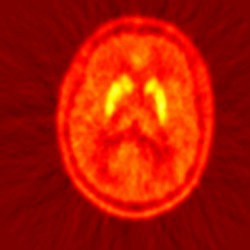

In the brain, dopamine functions as a neurotransmitter communicating information from one nerve cell to another. Changes to the brain’s capacity to make dopamine and excessive dopamine release are conducive to psychosis and schizophrenia. Despite knowing for decades that antipsychotics work to reduce dopamine release, it was only recently discovered that treatments actually target a slightly different area on the dopamine system to where the abnormality occurs. While this was a big advancement in the field, uncertainty ensued as to whether the abnormality was the primary cause for developing psychosis, or secondary to something else. Now, two new discoveries from the CSC’s Psychiatric Imaging Group delve deep into the dopamine system and provide novel insight into minds vulnerable to psychotic episodes.

In the first of the two studies, Dr. Oliver Howes and his team applied positron emission tomography (PET) and scanned for dopamine abnormalities in prodromal patients – those at risk of developing schizophrenia (20% to 40% risk of presenting a psychotic episode within 1 to 3 years). Published in Biological Psychiatry, the study revealed that patients presented dopamine abnormalities a year or so before they went on to developing schizophrenia. “This is first time we show that these abnormalities to the dopamine system are primary to developing schizophrenia,” explains Oliver.

The revelation also highlights dopamine as an early marker for impending schizophrenia. “People that had the highest dopamine levels showed the most severe symptoms,” reveals Oliver, “because the levels changed, progressively getting higher as the illness progressed, we can think about ways to target and prevent the increase in dopamine and subsequent disease onset.” Oliver’s team confirmed their findings by successfully replicating their results in a completely different cohort of people and using a different scanner.

For about 10% of people with schizophrenia, cannabis has played a role in either triggering the illness or bringing it on earlier. In a second study, Oliver’s team set out to investigate the role of cannabis in the development of schizophrenia. The study, also published in Biological Psychiatry, recruited cannabis users and applied PET to measure the effect cannabis had on the brain’s dopamine-making ability. “We selected people who became psychotic when they used cannabis and compared the scans with those who never or very rarely used,” he says, “we thought that those vulnerable to psychosis would show high levels of dopamine manufacture, similar to people at risk of schizophrenia.”

Surprisingly, dopamine levels were in fact lower. “This result is a bit of a game changer for theories in the field,” explains Oliver, “it says that in some people, the vulnerability to psychosis has nothing to do with dopamine.” Lower dopamine levels are exhibited in people with drug addictions to cocaine and amphetamines, and in this study may explain why people become addicted to cannabis and use more frequently. “As there is no relationship with dopamine and the psychotic symptoms that cannabis induces in them, it suggests that either other transmitter systems are at play, or these people are highly sensitive to changes to dopamine levels.” Oliver’s team is now keen to explore these two avenues to determine the route to psychosis, and subsequent targets for treatment.

YJ

References:

Egerton, A., Chaddock, C. A., Winton-Brown, T. T., Bloomfield, M. A., Bhattacharyya, S., Allen, P., McGuire, P. K., & Howes, O. D. (2013). Presynaptic striatal dopamine dysfunction in people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: findings in a second cohort. Biological Psychiatry, 74 (2), 106-112.

Bloomfield, M. A., Morgan, C. J., Egerton, A., Kapur, S., Curran, H. V., & Howes, O. D. (2014). Dopaminergic function in cannabis users and its relationship to cannabis-induced psychotic symptoms. Biological Psychiatry, 75 (6), 470-478.

These studies were funded by the Medical Research Council and the South London and Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre and a National Institute of Health Research Biomedical Research Council grant.

The Medical Research Council has been at the forefront of scientific discovery to improve human health. Founded in 1913 to tackle tuberculosis, the MRC now invests taxpayers’ money in some of the best medical research in the world across every area of health. Twenty-nine MRC-funded researchers have won Nobel prizes in a wide range of disciplines, and MRC scientists have been behind such diverse discoveries as vitamins, the structure of DNA and the link between smoking and cancer, as well as achievements such as pioneering the use of randomised controlled trials, the invention of MRI scanning, and the development of a group of antibodies used in the making of some of the most successful drugs ever developed. Today, MRC-funded scientists tackle some of the greatest health problems facing humanity in the 21st century, from the rising tide of chronic diseases associated with ageing to the threats posed by rapidly mutating micro-organisms. www.mrc.ac.uk