By Staff Member

July 28, 2015

Time to read: 6 minutes

Deborah Oakley

Scientists have shown that women may not need to “eat for two” during pregnancy because the body adapts to absorb more energy from the same amount of food. The findings may also help to explain why some women struggle to lose weight after giving birth.

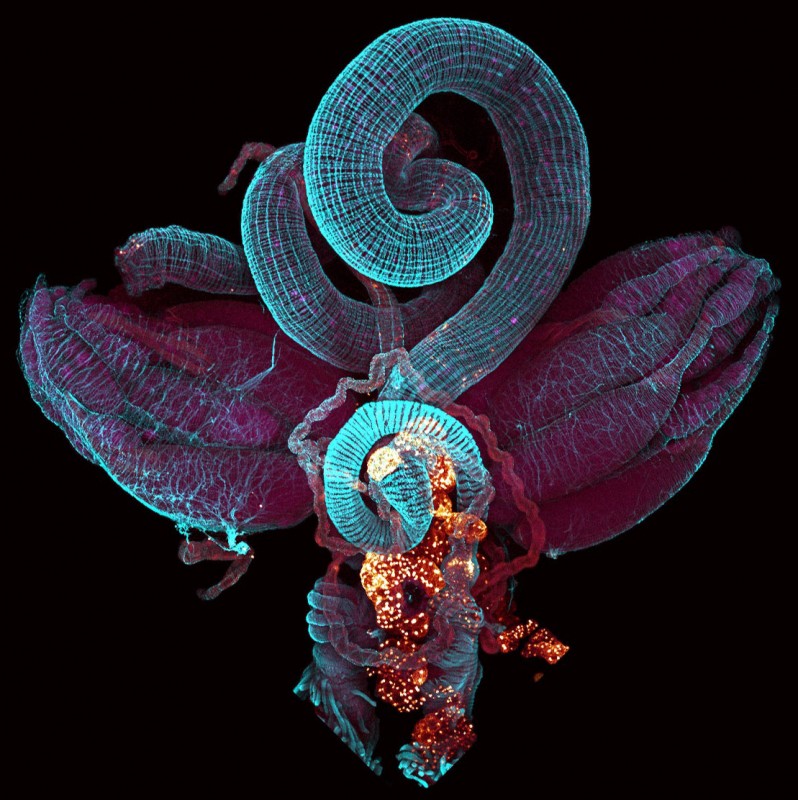

Researchers at the MRC’s Clinical Sciences Centre (CSC) based at Imperial College London are the first to show that a hormone released during pregnancy triggers the intestine to grow dramatically, and stimulates the mother’s body to store more fat.

“Previous studies have shown that eating for two during early pregnancy is unnecessary. Our research suggests that this is because the digestive system is already anticipating the demands that the growing baby will place upon our body,” says Irene Miguel-Aliaga, who is head of the CSC’s Gut Signalling and Metabolism Group, and who led the research.

“We normally think of our internal organs as being a fixed size, but the fact is that they are not. They can grow and change, and we show that this is important for making babies,” says Miguel-Aliaga.

The experiments were performed in fruit flies, and the team is hopeful that the results will translate to humans. Previous studies show that the intestines of many mammals – such as mice, rats and cows – grow during pregnancy. According to Miguel-Aliaga, this suggests that similar changes happen in humans.

“Many of the fly genes that we studied exist in humans, so our results are absolutely relevant,” says Jake Jacobson, who works alongside Miguel-Aliaga at the CSC and is a co-author on the paper, which describes their findings, published this morning in the journal eLife. “Flies also utilise and store fat like we do, and their metabolism is controlled by similar hormones,” Jacobson says.

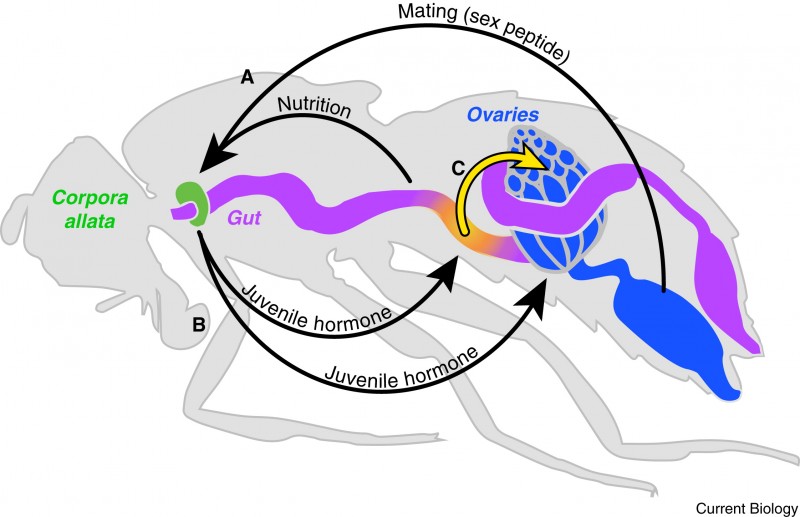

Although scientists have observed that the intestine grows in many mammals, it has not been clear exactly why this happens. Now the CSC team has shown that a fly hormone, called ‘juvenile hormone’, triggers the changes to the intestine and fat metabolism. Juvenile hormone acts in a similar way to human thyroid hormones, which regulate the body’s energy demands.

“We know that in humans, the levels of several hormones change during pregnancy, and that these changes can affect how our digestive system works” says Miguel-Aliaga. “We expect that these human hormones act in the same way that juvenile hormone does in flies, to resize the intestine and thus help the mother to extract more energy from her food.”

Scientists had previously thought that a woman’s appetite changed in response to the baby’s increasing demands for energy. Miguel-Aliaga says their research shows that this is not the full story. They have shown that levels of juvenile hormone begin to rise in female flies surprisingly early, in fact immediately after mating. This tells the intestine to rapidly adapt so that it is prepared to meet the energy needs of the fertilised eggs.

The researchers know that these metabolic changes do not happen because the mothers are eating extra food. They analysed a strain of sterile flies that cannot produce eggs, so do not become pregnant and cannot experience a prompt, if one exists, that might increase their appetite. They found that even these flies grew visibly larger intestines after mating.

The changes in metabolism appear in part to determine the success of fly pregnancy. “If we prevent juvenile hormone from changing the intestine, the flies produce fewer eggs. This hormone is key to the fly producing as many healthy eggs as possible,” says Miguel-Aliaga.

The research suggests that, in people, if hormone levels fail return to normal after birth, a mother’s intestine may remain abnormally large, so she will continue to extract extra energy from her food “Some women find it difficult to lose weight after pregnancy,” says Jacobson. “We may now have found a biological reason for this.”

In the long term, these metabolic changes may have more sinister consequences. In flies, juvenile hormone stimulates the intestine to grow by activating stem cells in the lining of the intestine. Stem cells have the potential to replicate an infinite number of times, and in people can cause cancer. Scientists know that pregnant women are more susceptible to some cancers. If the stem cells remain activated after pregnancy, they will continue to grow – and may ultimately form a tumour.

The researchers will now use mice – whose organs are similar to our own – to find out more about the functions of pregnancy-regulated hormones in humans.

Dr Joe McNamara, Head of Population and Systems Medicine at the MRC, added: “Studies in fruit flies have been very valuable in providing insights into human physiology. This research points to a new scientific explanation why eating for two during pregnancy is not necessary, and may even be harmful, as a growing body of evidence indicates that a mother’s diet can impact a child’s propensity to be obese in later life. The important next step will be to reproduce these findings in humans.”

The work was done in collaboration with Maria Dominguez, of Universidad Miguel Hernández in Spain, and Joanne Yew, of the National University of Singapore.

Read eLife’s ‘Insight’ article about the study.

To find out more and arrange interviews, get in touch:

Deborah Oakley

Science Communications Officer

MRC Clinical Sciences Centre

T: 0208 383 3791

M: 07711 016942

E:

Susan Watts

Head of Public Engagement & Communications

MRC Clinical Sciences Centre

T: 0208 383 8247

M: 07982 142327

E:

This week (17 August), Current Biology published a ‘Dispatch’ article about this research, titled ‘Female flies have the guts for reproduction’. Author Alexander Shingleton writes, “These new data bring our understanding of the hormonal regulation of reproduction in insects to a new and more profound level and put juvenile hormone at its core.”