By Sophie Arthur

May 13, 2019

Time to read: 3 minutes

Cancer is a disease that has affected us all in one way or another. Analysis by Cancer Research UK estimates that one in every two people will be diagnosed with cancer at some point during their lifetime now. It is not all bad news as more and more people are surviving cancer than ever before, but how would it make you feel if you survived the cancer, and then got told that you have now developed heart failure?

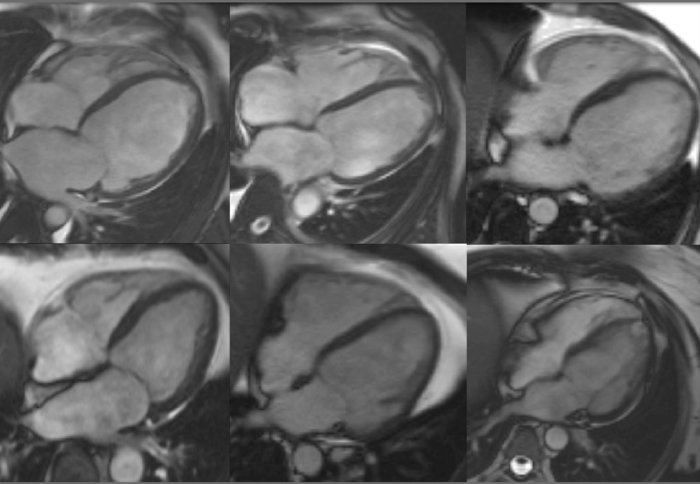

Chemotherapy is the most common treatment of fighting cancer and anthracyclines are a group of chemotherapy drugs that are widely used and highly effective, particularly for breast cancers, leukaemias and a number of other cancer types. However, a number of patients who survive their cancer after receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy go on to develop heart failure afterwards. The latest research from the Cardiovascular Genomics and Precision Medicine group at the MRC LMS has looked into why individuals develop heart failure after chemotherapy.

The research published on 16 April in the journal Circulation reveals that some individuals will have a genetic predisposition to this cancer therapy-induced cardiomyopathy, or heart failure.

The researchers analysed a number of genes that form the heart muscle, which are also associated with cardiomyopathy, in the recruited patients. They identified that many of the patients who had developed heart failure after chemotherapy carried variants of the cardiomyopathy genes that were the same as patients who suffer from inherited cardiomyopathy. Variants in one particular cardiomyopathy gene called Titin was one of the biggest contributors to this genetic predisposition; a gene which 1% of the population carry.

Is it time to switch up chemotherapy?

Anthracyclines are widely used in chemotherapy. For example, of the 1 in 6 individuals who will develop breast cancer, 1 in 3 will receive this class of drugs as their treatment, so huge numbers of people could be affected. However, anthracyclines are widely used because they are really effective. The results from this study are not to remove or reduce the use of anthracyclines in chemotherapy regimes, but instead will be highly valuable in identifying individuals who are at higher risk of cancer therapy side effects. This will allow clinicians to hopefully be able to put these patients under closer surveillance and with more personalised treatments.

James Ware, Head of the Cardiovascular Genomics and Precision Medicine group, discussed the next steps for this research:

“We are trying to understand the mechanisms by which this genetic predisposition interacts with chemotherapy and leads to cardiomyopathy, and are also evaluating how to use this information clinically. We need to determine whether identifying high risk patients leads to better outcomes, and the cost-effectiveness of implementing any new regimes. Finally, we still don’t understand why some patients with genetic predispositions develop problems, while others don’t”

‘Genetic variants associated with cancer therapy-induced cardiomyopathy’ was published in Circulation on 16 April. Read the article here.