By Sofia Velasquez-Pimentel

November 25, 2022

Time to read: 6 minutes

A recent publication from the LMS Psychiatric Imaging Group reviewed decades of research on TAAR1 as a potential drug target for schizophrenia.

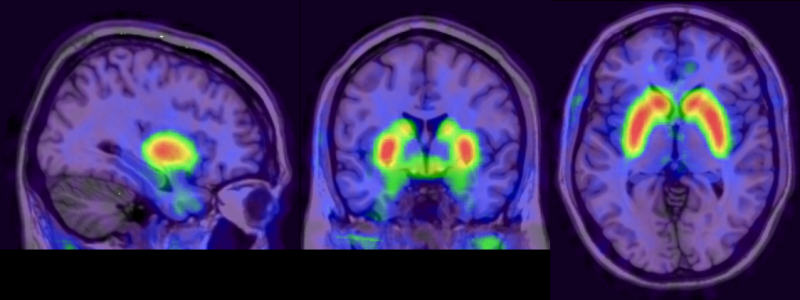

Brain dopamine synthesis shown through brain imaging using FDPOA PET (Positron Emission Tomography) by Molecular Imaging

Brain dopamine synthesis shown through brain imaging using FDPOA PET (Positron Emission Tomography) by Molecular Imaging

Schizophrenia is a long-term mental health condition affecting 1 in 100 people and is associated with symptoms including hallucinations, social withdrawal and difficulty problem-solving. There have been steps to treat schizophrenia, but current medications still cannot treat several symptoms and have significant side effects.

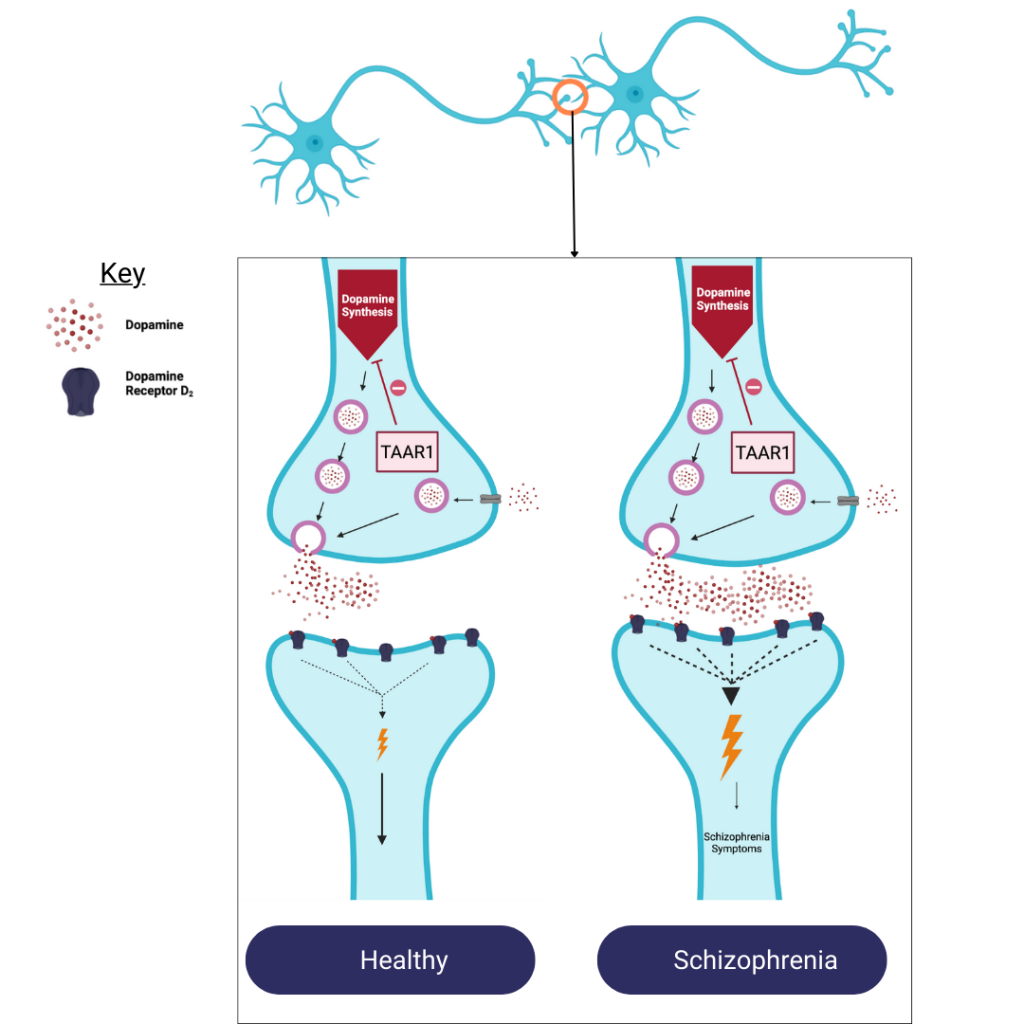

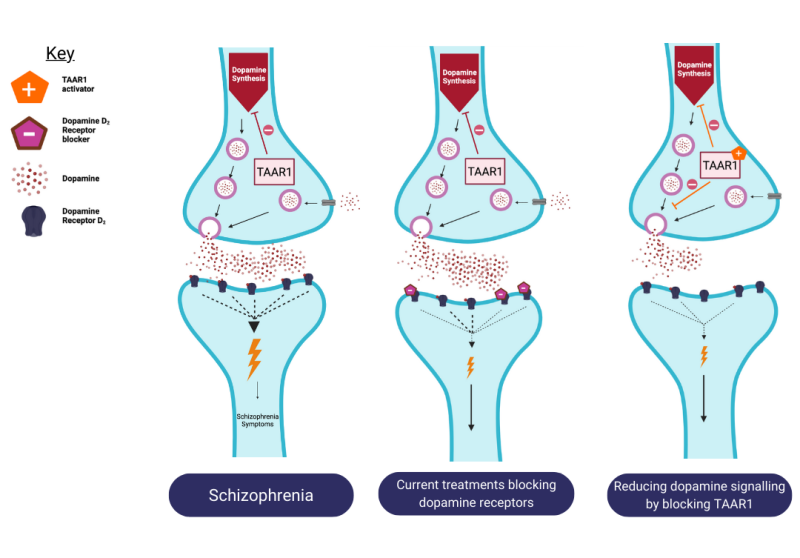

In schizophrenia, there is an excessive production, release, and activity of the brain’s chemical, also known as a neurotransmitter, dopamine. Excess dopamine activity results from altered regulation of two other neurotransmitters – serotonin and glutamate. Current treatments work by blocking the dopamine receptors on a type of brain cell (neurons) to minimise the dopamine signal from being passed on to neighbouring neurons.

Schizophrenia occurs when there is an excessive amount of the neurotransmitter dopamine released when neurons communicate compared to people who do not have schizophrenia. The more dopamine is received by the neighbouring neuron the greater the response. This increased response leads to schizophrenia symptoms.

Trace Amine-Associated Receptor1 (TAAR1), a receptor for the neurotransmitter trace amines, has become an increasingly attractive drug target because it can regulate dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate.

Given that TAAR1 is a promising new treatment target, a new publication from the MRC LMS’ Psychiatric Imaging Group reviewed decades’ worth of research and clinical trials to clarify the following:

Although antipsychotic medication is effective in treating ‘positive’ symptoms, including hallucinations and delusions, it does not treat ‘negative’ symptoms, including social withdrawal and/or the inability to experience emotion and ‘cognitive’ symptoms, including difficulty learning, reasoning, and problem-solving. Additionally, these treatments are ineffective in about 20% of people with schizophrenia and have significant side effects that increase a patient’s risk of developing diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

“There are lots of unmet needs in psychosis, and many people do not respond to drugs, so there is a need to develop better and more targeted treatments.”

– Dr Grazia Rutigliano, psychiatrist and researcher in the LMS Psychiatric Imaging Group

The psychiatric imaging group highlight part of the reason for this treatment profile is that drugs only target the downstream effects of excess dopamine signaling, but not the underlying neurobiology that leads to excess dopamine in the first place. This difficulty makes TAAR1’s ability to regulate dopamine, glutamate, and serotonin signalling an attractive mechanism to target.

Both TAAR1 and trace amines have been established as significant players in schizophrenia.

For example, genetic studies find that the TAAR1 gene is in the same region of DNA that is repeatedly associated with schizophrenia. Various genetic modification studies also suggest that in the absence of TAAR1 there is a higher activity of dopamine and serotonin. Without TAAR1 there is an exaggerated response to amphetamine, a drug that elevates dopamine and leads to schizophrenia symptoms.

In contrast, genetically engineered mice with above-normal amounts of TAAR1 have a dimmed response to amphetamine compared to normal mice. These studies indicate that TAAR1 has a significant involvement that influences the activity of the neurotransmitters involved in schizophrenia.

Studies find that targeting TAAR1 reduces the amount of dopamine made and reduces the amount of dopamine released. Targeting TAAR1 also corrects the dysregulated glutamate and serotonin signalling seen in schizophrenia. This method contrasts with the current approach that blocks dopamine transmission.

Current treatments block the receptors to prevent dopamine from binding to them which normalises the dopamine signal. However, activating TAAR1 blocks the production of dopamine which is an alternative way to regulate the excessive amount of synaptic dopamine in schizophrenia.

Animal studies find that different drugs targeting TAAR1 successfully reduced hyperactivity Excitingly, targeting TAAR1 was also able to attenuate social withdrawal, taken as a model of ‘negative’ symptoms.

“Currently available antipsychotic drugs only target downstream consequences of dopamine excess. Research in animals shows that drugs that target TAAR1 have the potential to act much closer to the actual cause of dopamine overactivity, and may also help improve symptoms that currently used drugs do not affect.”

– Dr Els Halff, lead author and researcher in the LMS Psychiatric Imaging Group

Targeting TAAR1 successfully improved attention and focus, without adverse side effects such as motor impairments, catalepsy, or weight gain. In mice, it also reduced impulsive behaviour. These effects may be related to the modulation of glutamate activity. In other studies, with rodents and monkeys, drugs that targeted TAAR1 also showed properties that could reduce anxiety and depression, both of which are associated with the activity of serotonin.

After having successfully identified targets and seen promising effects in animals two drugs that are currently in clinical trials to test their effect in people with schizophrenia.

The first drug, Ulotaront, was effective in people with schizophrenia with a very low rate of side effects compared to current antipsychotic medication. This drug has progressed to the third of the four clinical trial phases to test the safest dose.

The data from animal models that mimic schizophrenia suggest that activating TAAR1 can be beneficial not only for ‘positive’ symptoms but, unlike current medications, can improve ‘negative’ symptoms and cognitive symptoms as well. This has led to the development of drugs that have progressed through clinical trials to be effective without the side effects commonly seen with current antipsychotic medication. Taken together, the Psychiatric Imaging Group highlighted TAAR1 as a potential new treatment strategy that could better target the neurobiology that underlies this disorder. This review highlights the progress that has been made in understanding TAAR1 and the application of animal studies to humans. However, there is more work to be done to better meet the needs of people with schizophrenia.

This review was published in Trends in Neuroscience, Cell Press and was led by Oliver Howes in the MRC LMS’ Psychiatric Imaging Group. This research was conducted by researchers at the MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences in collaboration with Imperial College London and King’s College London.

This blog was written by Sofia Velazquez Pimentel