By Helen Figueira

April 1, 2016

Time to read: 9 minutes

Susan Watts

It sounded straightforward: “What should be our scientific strategy? Where are the opportunities? And who should we be bringing to the CSC to help us with this?” Clear goals from the CSC’s Matthias Merkenschlager, co-organiser, along with Oliver Howes, of a unique workshop earlier this month.

What followed was anything but straightforward. Attendees found themselves on an exhilarating two-day journey through the very latest thinking in experimental and computational biology. This began at the Wellcome Collection in central London on the evening on Friday 4 March, followed by a series of talks the following day at the CSC’s home at the Hammersmith Hospital campus of Imperial College.

Groups working on Integrative Biology (IB) have reached a critical mass at the CSC. Late last year, a new IB section won strategic backing from the UK’s Medical Research Council, to bring to bear both experimental and computational methods in tackling scientific questions. The workshop served both as a celebration and as a way of looking to the future, including bringing in new groups.

With the intriguing backdrop of the Wellcome medical collection, scientists first heard from Nikolaus Rajewsky of the Max Delbruck Centre (MDC) in Berlin and Stuart Cook of the CSC. Rajewsky talked about his work on circular RNA, which he has found in surprising abundance in neurons. He discussed the joys of “droplet sequencing” as a method he claimed can provide sequencing data some two orders of magnitude cheaper than current techniques.

Stuart Cook described his quest to understand a paradox: namely that some one per cent of the world’s population carry a genetic mutation known to be linked to heart disease, with no apparent effect. The key, he thinks, is that the hearts of such people may be “primed to fail” if they suffer a second hit, whether genetic or environmental. By his reckoning, there are some 30 million people in this position globally; a potential target group, he said, for preventative drug approaches.

Andrew Pospisilik, of the Max Planck Institute in Freiburg in Germany, described his latest work in flies to examine the effect of paternal diet on offspring. He has found that in flies that are genetically the same, exposure of the father to different nutrition changes the outcome for offspring. He’s noted that in flies there appear to be two populations, those that become obese and those that do not. He’s intrigued by a similar pattern that appears to occur in people as he observes current trends in childhood obesity. “What happened in the US is not that the population got obese, but a sub-population got obese.”

On Saturday, Jan Korbel of EMBL Heidelberg, spoke about his work on structural variation in the genome. He has devised efficient ways to map structural variation, and suggests that structural alterations that cannot be explained by gradual mutational change could instead be down to chromosomes being shattered, then repaired, during the cell cycle.

He spoke too about rapid advances in the speed of genome sequencing, and its plummeting cost. He said re-working by the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) has allowed his team to pursue fresh research lines, but how to store and manipulate the volume of data this generates is proving one of his biggest challenges. “Many of us who are using large datasets will be hit with the need for outside resources”. He’s exploring the use of hybrid cloud computing set-ups, making use of an Amazon service. He proposed further thought about the need for a Europe-wide cloud computing service.

Michael White, of the University of Manchester, began his talk with a quote from Sir John Maddox (editor of Nature from 1966 to 1973 and 1980-1995). In a critical commentary published in 1992, Sir John said: “molecular biology seems well on the way to becoming a largely qualitative science.” But White cited CRISPR gene editing technology as a turning point: “Probably the biggest change we’ve seen in this field for many, many years,” he said. Today’s approach is quite different: “Eventually we want to quantify everything. We have a massive quantitative challenge, and we’re certainly not there yet.”

He described his work on imaging the genes in single cells as they switch on and off. “We need to understand what is happening at a single cell level to understand the tissue,” he told the audience. He went on to discuss his work on the rhythms, oscillations and “clocks” at play inside the cell. He’s looking for clues about the physiological importance of the pulsing he observes, by trying to understand more about how this is affected by change in external factors such as temperature and drugs, homing in, he said, on “a set of genes that we believe are frequency controlled”

Jan Skotheim, of Stanford University School of Medicine, defined the question at the heart of his work: “how do cells decide to divide or not divide?” A physicist by training, Skotheim thinks there’s much to be said for somebody outside of a discipline coming in to take a look. And he made an appeal: “You have to be quite understanding of people from other fields. They might seem like idiots now, but later they might contribute something that other people didn’t.”

He quoted JBS Haldane’s On Being the Right Size: “The most obvious differences between different animals are differences of size, but for some reason the zoologists have paid singularly little attention to them. In a large textbook of zoology before me I find no indication that the eagle is larger than the sparrow, or the hippopotamus bigger than the hare, though some grudging admissions are made in the case of the mouse and the whale. But yet it is easy to show that a hare could not be as large as a hippopotamus, or a whale as small as a herring. For every type of animal there is a most convenient size…”

This has been his guiding thought, he said, as he explores cells to look for proteins that might prove the rate-limiting focus of the cell cycle, when it comes to growth. “If you’re trained in one discipline and you want to move into another, it’s like moving to a foreign country where they don’t speak your language and where you have to work out what the hell everyone is saying.” It was only after having overcome this initial hurdle, he said, that he made progress on his central question, using time-lapse imaging to watch growing and dividing yeast cells. “Seeing the chemistry going on in single cells is very exciting.”

After lunch, Lucas Pelkmans, of the University of Zurich, described his work on predicting transcription abundance in cells. In a recent paper in Cell, he showed that variation in gene expression between cells is not “stochastic” but can be predicted, based on features such as size and shape. He also showed that the cell nucleus acts as a kind of buffer: that transcription happens in bursts with transcripts staying in the nucleus for a while, then released to the cytoplasm slowly, keeping RNA levels in the cytoplasm relatively constant.

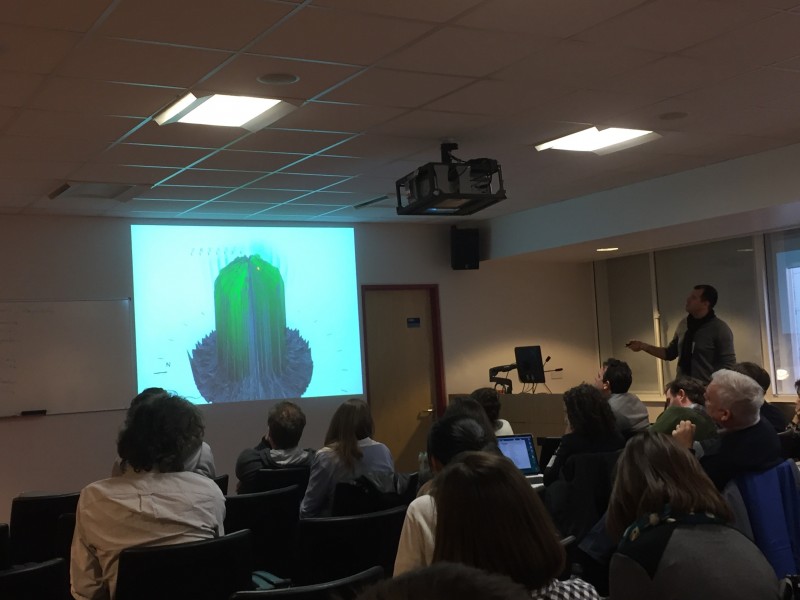

Fyodor Kondrashov, of the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona, showed what he described as “the first video representation of a fitness landscape of many, many genotypes.” Kondrashov, who has an EMBO Young Investigator Award, described new ways to visualise the process of evolution, and how it changes with context.

Several CSC scientists presented their research during the course of the workshop: David Rueda described his use of cutting-edge microcopy techniques with single-molecule resolution to show how an enzyme crucial to keeping our immune system healthy “surfs” along strands of DNA inside our cells. Boris Lenhard talked about the organisation of regions of DNA, for example showing the genome regulatory blocks (GRBs) and topologically associated domains (TADs) show a similar distribution, and that GRB boundaries predict TAD boundaries across cell types.

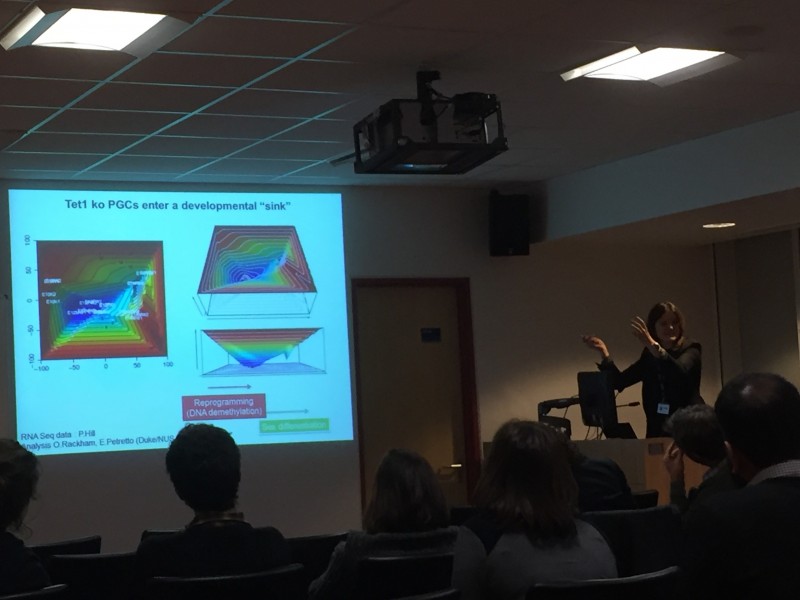

Irene Miguel-Aliaga described her work on the sexual identity of our organs, using the fruit fly model. Simona Parrinello talked about mechanisms behind the behaviour of glioblastoma cells in brain tumours. Silvia Santos presented a story on a newly found strategy used by cells to control the time at which they divide, combining quantitative experimental approaches and mathematical modelling. Andre Brown described his work with nematode worms, looking for observable changes in phenotype after exposure to a drug that might indicate the mechanism of that drug. And EMBO Young investigator award winner Petra Hajkova drew the meeting to a close with a talk on epigenetic memory in the developing embryo.

Amanda Fisher, director of the CSC, summed up the spirit of the two-day gathering: “It’s such a great chance to ask all these talented young scientists what they think we should be doing in the future.” And with talks ranging widely from the very experimental to very theoretical, there proved fertile ground for discussion and debate. Excited conversation filled all of the breaks, and there was barely enough time to finish the programme. One scientist said the experience left them with a “scientific hangover” the next day; a feeling of having consumed so much, and being left a little overwhelmed at the prospect of further scientific endeavour.

For co-organiser Oliver Howes, the workshop showed the value of quantitation, as well as the importance of developing ways to handle increasingly large datasets and linking these to robust experimental testing. “Integrating the experimental and the computational is the next challenge, and future recruitment at the CSC and elsewhere will reflect this new frontier,” he said.

There was strong agreement that the workshop should be repeated to monitor progress. For some, the two day’s of talks showed just how much has changed in the couple of decades since Sir John Maddox raised concerns over a lack of a quantitative future for biology, and began to sketch out the very much quantified journey that lies ahead.

Contact

Susan Watts

Head of Communications and Public Engagement

MRC Clinical Sciences Centre

L: 0208 383 8247

M: 07590 250652

E: