Researchers at the MRC Laboratory of Medical Sciences (LMS) have discovered the expression of a cancer-causing gene in an unexpected part of the intestine.

The finding, published in The EMBO Journal, is significant because it suggests that this new function of the so-called Ret receptor gene is evolutionarily conserved from flies to mice and may therefore have implications for the treatment of intestinal disease and bowel cancer in humans.

Ret receptor tyrosine kinase is a normal gene that regulates cell growth in the enteric nervous system, but loss of Ret function can lead to a gut disorder in babies known as Hirschsprung’s disease while overexpression of the gene has been found in various types of cancer.

Professor Irene Miguel-Aliaga, who led the work at LMS, explained that scientists have known for over 20 years that Ret expression was a defining feature of enteric neurons.

‘Our research is the first time that it has been noticed in the gut outside of nerve or immune cells, in a different cell population: the intestinal epithelium,’ she added.

The epithelium is a layer of cells in the lining of the intestine that absorbs food and acts as a barrier against harmful substances. Unlike neurons, epithelial cells regenerate constantly throughout adult life and need Ret to sustain proliferation.

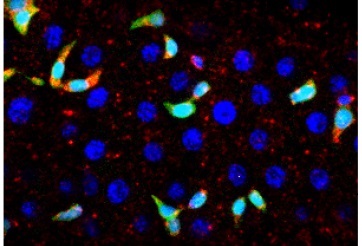

Microscopic images of Ret-positive epithelial cells (in red, co-stained with an adult progenitor marker in green) in the midgut of an adult fly.

Miguel-Aliaga launched the research project seven years ago with the initial aim of discovering if similar mechanisms were active in mammalian and invertebrate gut neurons. She used fruit flies as a primary tool because of their genetic similarity to humans. Over 60% of our genes have equivalent counterparts in flies.

‘We were curious to see if the gut neurons in flies and humans are wired in the same way, if the same genes are responsible for getting nerve cells to the gut in both species,’ she said.

‘And we did find Ret expression in fly neurons but while we were looking we also found that Ret was expressed in an unexpected place, and the unexpected place was the actual epithelium of the gut itself.’

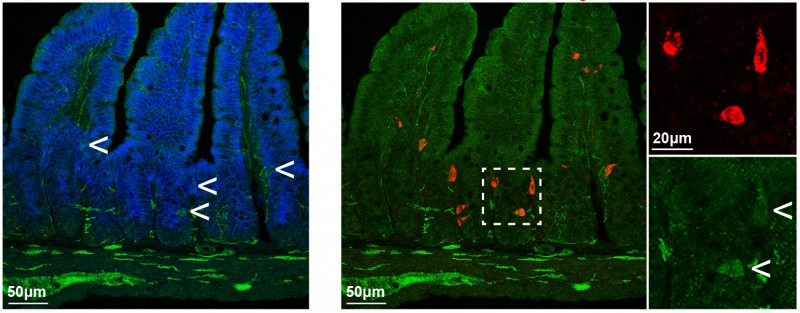

Further experiments revealed that epithelial expression of Ret is not confined to the fly intestine but also occurs in the developing intestinal epithelium of mice where its expression persists into adult stage in a subset of enteroendocrine/enterochromaffin cells which, based on recent research, may have stem-cell like properties.

‘At first we were puzzled because there seemed to be a discrepancy between the fly and mouse data,’ Miguel-Aliaga said. ‘In adult flies Ret is expressed in epithelial stem cells but in mice we found it was expressed in their progeny, the enteroendocrine cells. Now we think that Ret may be doing the same thing in both epithelia, playing a key role in signalling pathways that control proliferation and maturation.’

The LMS study could have significant clinical implications because its findings raise the possibility that if epithelial expression of Ret is conserved in humans, dysregulation of epithelial signalling may contribute to human diseases such as Hirschsprung’s or gastrointestinal tumours.

Miguel-Aliaga described the research project as a ‘big team effort’ involving ‘multiple countries, multiple researchers and many years’.

‘I think maybe the lesson is that it takes time to find new things and to show that they’re evolutionarily conserved,’ she added. ‘Initially we were looking for something else. We found something unexpected, then it took us a while to figure out if that something was important in flies. And once we’d figured out that it was important in flies, it took us two more years to show a function in mice, which are closer to us.

‘Obviously the next step will be for somebody to work out whether it’s important in humans too. It’s only the beginning. There is still a lot of work to do.’

Microscopic images of Ret-positive epithelial cells (in green, co-stained with an enteroendocrine marker in red) in the mouse intestinal epithelium (in blue)