Professor Oliver Howes’ research focuses on understanding the causes of mental illness and pioneering the use of positron emission tomography (PET) and other imagining techniques to better understand, diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions. Since joining the LMS in 2009, his research has been going from strength to strength, highlighted by over 20 publications in the past year alone, and culminating in the recent award from the Royal College of Psychiatrists “It’s a huge honour” said Howes, speaking the day after picking up the prestigious trophy. “It’s recognition not just for me, but for what the whole team has achieved”.

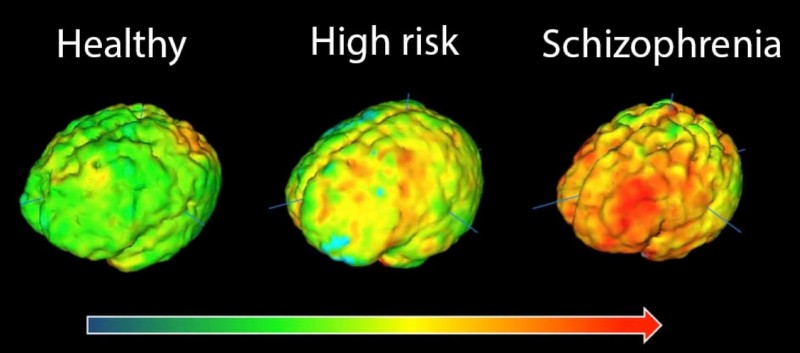

Brain images showing elevation in microglial activity in orange/red. The highest levels in schizophrenia are in the frontal cortex and the temporal cortex.

Photograph: MRC Laboratory of Medical Sciences

A major focus of Howes’ research is schizophrenia; affecting 1 in 100 people, it is a severe mental illness with symptoms ranging from memory and cognitive problems, to auditory and visual hallucinations. A pioneering new trial, led by the Howes team, is currently exploring for the first time the potential use of immunotherapy for treatment of schizophrenia.

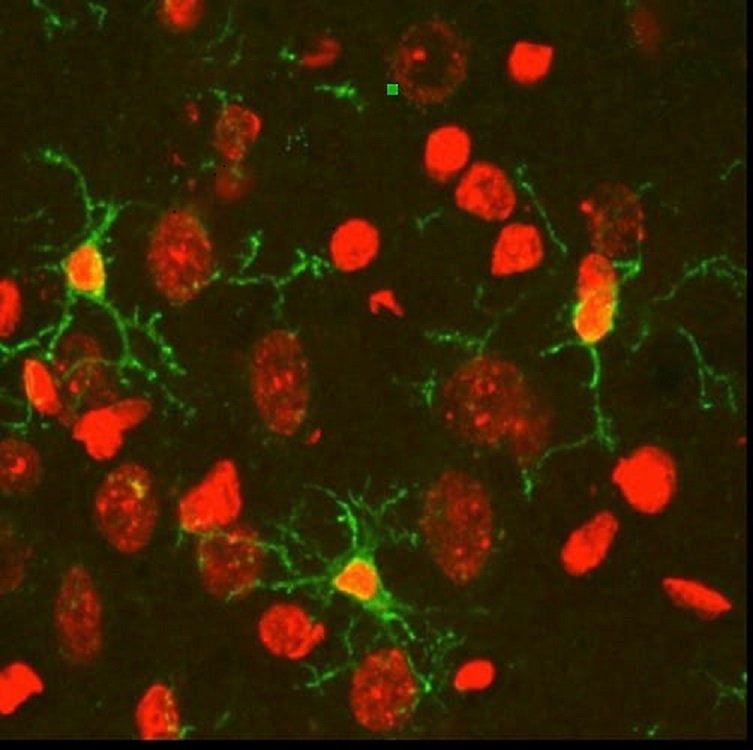

The basis for the new trial, which was reported recently in the Guardian, comes from Howes’ previous work indicating that the development of schizophrenia may be linked to neuroinflammation in the frontal cortex. Previous studies have implicated the role of resident immune cells, microglia, in the pathology of psychosis. It is hypothesised that unregulated synaptic pruning by the microglia results in reduced cortical and grey matter volume. This area of the brain indirectly controls the levels of dopamine and delusions and paranoia experienced by patients are attributed to the surge in this neurotransmitter.

Using PET and a radioligand specific for a microglial marker, Howes’ team found that schizophrenic patients have elevated microglial activity in grey matter compared with healthy control subjects. Furthermore, the increase in microglial activity correlated with the severity of the patients’ psychotic symptoms. Most encouraging was the finding that patients which had not yet experienced a psychotic episode but were characterised as high-risk, had parallel increases in microglial activity compared to controls. Additionally, a patient initially identified as high risk who subsequently experienced their first psychotic episode, was found to have the highest level of microglial activity relative to the others in the patient group. Taken together, these data indicate that microglial activity could be used as a tool to identify high-risk individuals and opens up the possibility to treat patients prior to the onset of psychosis.

Microglial cells, outlined in green stain, have thin processes that reach out around brain cells, stained in red.

Photograph: Bloomfield et al

Building on their findings, the team is now trialling an immunotherapy currently used for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS). In MS, a comparable unregulated activity of the immune system attacks the brain and so it is hypothesised the drug may be similarly beneficial for schizophrenic patients by targeting the hyperactive microglial cells. The drug, Natalizumab, is a humanised monocolanal antibody that targets α4-integrin, thereby reducing the ability of immune cells to migrate from the vasculature system.

This is potentially a very exciting step forward in the treatment of schizophrenia. As Howes explained: “Current options for treatment primarily target the dopamine receptors in order to control the psychotic symptoms after the brain is already damaged. This approach has the potential to identify high risk individuals and prevent the damage to the brain in the first instance. In addition, if it demonstrates a key role for inflammation in the progression of schizophrenia, it will open up doors for the trials of other immunotherapies”.